Our Suggested Guide of Pompeii, Part 3

Amalfi Coasting selected excerpts from “POMPEII: ITS LIFE AND ART”, by German archeologist August Mau, which is considered one of the best books ever written about Pompeii in terms of historical narrative and archeological facts and explanation. This is Part 3 of our excerpts.

THE HOUSE OF THE TRAGIC POET/CASA DEL POETA TRAGICO (#22 on the map)

In the "Last Days of Pompeii" the house of the Tragic Poet is presented to us as the home of Glaucus. Though not large, it was among the most attractive in the city.

It received its present form and decoration not many years before the eruption, apparently after the earthquake of 63, and well illustrates the arrangements of the Pompeian house of the last years.

The house received its name at the time of excavation, in consequence of a curious misinterpretation of a painting—now in the Naples Museum—which was found in the tablinum.

The subject is the delivery to Admetus of the oracle which declared that he must die unless some one should voluntarily meet death in his place.

The subject is the delivery to Admetus of the oracle which declared that he must die unless some one should voluntarily meet death in his place.

The excavators thought that the scene represented a poet reciting his verses; and since they found, in the floor of the tablinum, a mosaic picture in which an actor is seen making preparations for the stage, they concluded that the figure with the papyrus in the wall painting must be a tragic poet.

The plan does not differ materially from that which we have found in the houses of the pre-Roman time. In the floor of the fauces, immediately behind the double front door, is a dog, attached to a chain, outlined in black and white mosaic, with the inscription, cave canem, 'Beware of the dog!' The picture was for many years in the Naples Museum.

The black and white mosaic is well preserved in the atrium, the tablinum, and the dining room opening on the peristyle, as well as in the fauces.

The decoration of the large dining room is especially effective.

In the front of the room is a broad door opening into the colonnade of the peristyle; each of the three sides contains three panels, in the midst of a light but carefully finished architectural framework. In the central panels are large paintings: a young couple looking at a nest of Cupids; Theseus going on board ship, leaving behind him the beautiful Ariadne; and a composition in which Artemis is the principal figure.

In four of the smaller panels are the Seasons, represented as graceful female figures hovering in the air; the others present youthful warriors with helmet, shield, sword, and spear, all well conceived and executed with much delicacy.

The atrium, unlike most of those at Pompeii, was rich in wall paintings. Six panels, more than four feet high, presented a series of scenes from the story of the Trojan war, as told in the "Iliad." In arranging the pictures, the decorators had little regard for the order of events.

The subjects were the Nuptials of Zeus and Hera (at a on the plan); the judgment of Paris—though this is doubtful, as the picture is now entirely obliterated; the delivery of Briseis to the messenger of Agamemnon; the departure of Chryseis, and seemingly Thetis bringing arms across the sea to Achilles.

Half of the painting in which Chryseis appears was already ruined at the time of excavation; the other half was transferred to the Naples Museum, together with the paintings that were best preserved, the Nuptials of Zeus and Hera, and the sending away of Briseis.

The two pictures last mentioned are among the best known of the Pompeian paintings, and have often been reproduced. In one we see Zeus sitting at the right, while Hypnos presents to him Hera, whose left wrist he gently grasps in his right hand as if to draw her to him. Hera seems half reluctant, and her face, which the artist, in order to enhance the effect, has directed toward the beholder rather than toward Zeus, is queenly in its majesty and power.

A higher degree of dramatic interest is manifested in the other painting. In the foreground at the right, Patroclus leads forward the weeping Briseis. In the middle Achilles, seated, looks toward Patroclus with an expression of anger, and with an impatient gesture of the right hand directs him to deliver up the beautiful captive to the messenger of Agamemnon, who stands at the left waiting to receive her. Behind Achilles is Phoenix, his faithful companion, who tries to soften his anger with comforting words. Further back the helmeted heads of warriors are seen, and at the rear the tent of Achilles.

Another painting worthy of more than passing mention was found on a wall of the peristyle, and removed to the Naples Museum. The subject is the sacrifice of Iphigenia, who was to be offered up to Artemis that a favorable departure from Aulis might be granted to the Greek fleet assembled for the expedition against Troy.

At the right stands Calchas, his sheath in his left hand, his unsheathed sword in his right, his finger upon his lips. The hapless maid with arms outstretched in supplication is held by two men, one of whom is perhaps Ulysses.

At the left is Agamemnon, with face averted and veiled head, overcome with grief. Beside him leans his scepter, and on a pillar near by we see an archaic statue of Artemis with a torch in each hand, a dog on either side. Just as the girl is to be slain, Artemis appears in the sky at the right, and from the clouds opposite a nymph emerges bringing a deer, which the goddess accepts as a substitute.

HOUSE OF SALLUST/CASA DI SALLUSTIO (#25)

The house of Sallust received its name from an election notice, painted on the outside, in which Gaius Sallustius was recommended for a municipal office. It has no peristyle, and its original plan closely resembled that of the house of the Surgeon.

It was built in the second century B.C.; the architecture is that of the Tufa Period, and the well preserved decoration of the atrium, tablinum, alae, and the dining room at the left of the tablinum is of the first style.

The pilasters at the entrances of the alae and the tablinum are also unusually well preserved; the house is among the most important for our knowledge of the period to which it belongs. The rooms on the left side were used as a bakery. The rooms at the right were private apartments added later and connected with the rest of the house only by means of the corridor.

At the rear was a garden on two sides (24, 24'), with a colonnade. A broad window in the rear of the left ala opened into this colonnade, a part of which was afterwards enclosed, making two small rooms.

At the end of the latter room a stairway was built leading to chambers; in the beginning the house had no second floor. In the corner of the garden is an open air triclinium, over which vines could be trained; there was a small altar near by. A jet of water spurted from an opening in the wall upon a small platform of masonry.

Only the edges of this portion of the garden, which is higher than the floor of the colonnade, were planted. The large dining room may once have belonged to the bakery; the anteroom leading to it was made from one of the side rooms of the atrium. The proportions of the atrium are monumental.

The treatment of the entrances to the tablinum and the alae, with pilasters joined by projecting entablatures, the severe and simple decoration, and the admission of light through the compluvium increased the apparent height of the room and gave it an aspect of dignity and reserve.

The treatment of the entrances to the tablinum and the alae, with pilasters joined by projecting entablatures, the severe and simple decoration, and the admission of light through the compluvium increased the apparent height of the room and gave it an aspect of dignity and reserve.

There was a small fountain in the middle of the little garden, the rear wall of which is covered by a painting representing the fate of Actaeon, torn to pieces by his own hounds as a penalty for having seen Diana at the bath.

At first the colonnade had a flat roof, with an open walk above on the three sides; but when the large dining room was constructed, the flat roof and promenade on this side were replaced by a sloping roof over the broad entrance to the dining room.

On the outer walls of the two sleeping rooms were two paintings of similar design, Europa with the bull, Phrixus and Helle with the ram.

This portion of the house probably dates from the latter part of the Republic; it underwent minor changes in the course of the century during which it was used. The changes made in the stately house of the pre-Roman time are most easily explained on the supposition that near the beginning of the Empire it was turned into a hotel and restaurant.

The shop at the left of the entrance opens upon the atrium as well as on the street; the principal counter is on the side of the fauces, and near the inner end is a place for heating a vessel over the fire. Large jars were set in the counter, and there was a stone table in the middle of the room. Here edibles and hot drinks were sold to those inside the house as well as to passers-by.

This explanation is confirmed by the close connection of the bakery with the house; and the use of the open-air triclinium is entirely consistent with it.

VILLA OF DIOMEDES/VILLA DI DIOMEDE (#29 )

Two classes of villas were distinguished by the Romans,—the country seat, villa pseudo-urbana, and the farmhouse, villa rustica. The former was a city house, adapted to rural conditions; the arrangements of the latter were determined by the requirements of farm life.

The country seats manifested a greater diversity of plan than the city residences. They were relatively larger, containing spacious colonnades and gardens; as the proprietor was unrestricted in regard to space, not being confined to the limits of a lot, fuller opportunity was afforded for the display of individual taste in the arrangement of rooms.

We can understand from the letters of Pliny the Younger, describing his two villas at Laurentum and Tifernum Tiberinum (now Città di Castello), and from the remains of the villa of Hadrian at Tivoli, how far individuality might assert itself in the planning and building of a country home.

The main entrance of a country seat, according to Vitruvius, should lead directly to a peristyle; one or more atriums might be placed further back.

The main entrance of a country seat, according to Vitruvius, should lead directly to a peristyle; one or more atriums might be placed further back.

The living rooms would be grouped about the central spaces in the way that would best suit the configuration of the ground and meet the wishes of the owner.

In most parts of Italy a large farmhouse would contain appliances for making wine and oil.

The arrangement of the two types of country house in the vicinity of Pompeii may be briefly illustrated by reference to an example of each, the villa of Diomedes and the farmhouse at Boscoreale.

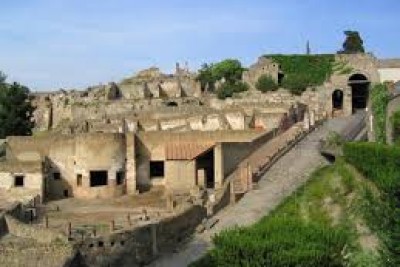

Villa of Diomedes is located beyond the last group of tombs at the left of the road leading from the Herculaneum Gate. An extensive establishment similar in character, the so-called villa of Cicero, lies nearer the Gate on the same side of the road; on the right there is a third villa, of which only a small part has been uncovered.

The three seem to have belonged to a series of country seats situated on the ridge that extends back from Pompeii in the direction of Vesuvius.

The villa of Diomedes, excavated in 1771-74, received its name from the tomb of Marcus Arrius Diomedes, facing the entrance, on the opposite side of the Street of Tombs.

We assume that the villa was built in Roman times, but before the reign of Augustus.

In front of the door was a narrow porch. The door opened directly into the peristyle, in the middle of a garden.

At the left is a small triangular court containing a swimming tank and a hearth on which a kettle and several pots were found; the Romans partook of warm refreshments after a bath.

The wall back of the swimming tank was in part decorated with a garden scene, not unlike those in the frigidariums of the two older public baths.

Over the tank was a roof supported by two columns, and on the other two sides of the court there was a low but well proportioned colonnade. The arrangements of the bath were unusually complete, comprising an apodyterium, a tepidarium, and a caldarium. A small oven stands on one end of the hearth in the kitchen, and a stone table is built against the wall on the long side.

The room in the corner was used as a reservoir for water, which was brought into it by means of a feed pipe and thence distributed through smaller pipes leading to the bath rooms and other parts of the house.

At the left of the peristyle is a passage leading to a garden. The large room at the rear of the peristyle may be loosely called a tablinum; it could be closed at the rear.

Back of the tablinum was originally a colonnade, which was later turned into a corridor, with rooms at either end. Beyond the colonnade was a broad terrace extending to the edge of the garden.

It commanded a magnificent view of Stabiae, the coast in the direction of Sorrento, and the Bay. Connected with it was an unroofed promenade over the colonnade surrounding the large garden below.

A rectangular room, indicated on the plan but not in the restoration) was afterwards built on the terrace. Members of the family could pass into the lower portion of the villa by means of a stairway, the slaves could use a 359 long corridor, which was more directly connected with the domestic apartments.

The flat roof of the quadrangular colonnade was carried on the outside by a wall, on the inside by square pillars. The rooms opening into the front of the colonnade were vaulted, and the decoration, in the last style, is well preserved.

At the opposite corners of the colonnade were two airy garden rooms.

The garden enclosed by the colonnade was planted with trees, charred remains of which were found at the time of excavation. In the middle was a fish pond, in which was a fountain.

The door at the rear of the garden led into the fields. Near it were found the skeletons of two men. One of them had a large key, doubtless the key of this door; he wore a gold ring 360 on his finger, and was carrying a considerable sum of money—ten gold and eighty-eight silver coins. He was probably the master of the house who had started out, accompanied by a single slave, in order to find means of escape.

At the time of the eruption many members of the family took refuge in the cellar. Here were found the skeletons of eighteen adults and two children: at the time of excavation the impressions of their bodies, and in some instances traces of the clothing, could be seen in the hardened ashes.

Among the women was one adorned with two necklaces and two arm bands, besides four gold rings and two of silver. The victims were suffocated by the damp ashes that drifted in through the small windows.

According to the report of the excavations, fourteen skeletons of men were found in other parts of the house, together with the skeletons of a dog and a goat.

VILLA OF THE MYSTERIES (#30)

Covered with ash and other volcanic material, the villa sustained only minor damage in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, and the majority of its walls, ceilings, and most particularly its frescoes survived largely undamaged.

The Villa is named for the paintings in one room of the residence. This space may have been a triclinium, and is decorated with very fine frescoes. Although the actual subject of the frescoes is debated, the most common interpretation of the images is scenes of the initiation of a woman into the cult of Dionysus, a mystery cult that required specific rites and rituals to become a member.

Room of the triclinium

Room of the triclinium

Paul Veyne believes instead that it depicts a young woman undergoing the rites of marriage.

The Villa had rooms for dining and entertaining and more functional spaces.

A wine-press was discovered when the Villa was excavated and has been restored in its original location. It was not uncommon for the homes of the very wealthy to include areas for the production of wine, olive oil, or other agricultural products, especially since many elite Romans owned farmland or orchards in the immediate vicinity of their villas.

The ownership of the Villa is unknown, as is the case with many private homes in the city of Pompeii. However, a bronze seal found in the villa names L. Istacidius Zosimus, a freedman of the powerful Istacidii family. Scholars have proposed him as the owner of the Villa or overseer of reconstruction after the earthquake of 62. The presence of a statue of Livia, wife of Augustus, has caused some historians to instead declare her to be the owner.

CENTRAL BATHS/TERME CENTRALI (#35)

Seneca in an entertaining letter gives an account of a visit about 60 A.D. to the villa at Liternum in which the Elder Scipio had lived in the years immediately preceding his death, in 183 B.C.

The philosopher was particularly struck with the bath, the simplicity of which he contrasts forcibly with the luxurious appointments of his own time.

We cannot follow him through the extended disquisition—he speaks of various refinements of luxury of which we find no traces at Pompeii; but he mentions as the most striking difference the lack of light in the old bath, with its small apertures more like chinks than windows, while in his day the baths were provided with large windows protected by glass, and people 'wanted to be parboiled in full daylight,' besides having the enjoyment meanwhile of a beautiful view.

Some such feeling as this we have in turning from the two older baths at Pompeii—one of pre-Roman origin, the other dating from the time of Sulla—to the Central Baths, which were in process of construction at the time of the eruption, and had been designed in accordance with the prevailing mode of life. Entrances from three streets lead to the ample palaestra.

Some such feeling as this we have in turning from the two older baths at Pompeii—one of pre-Roman origin, the other dating from the time of Sulla—to the Central Baths, which were in process of construction at the time of the eruption, and had been designed in accordance with the prevailing mode of life. Entrances from three streets lead to the ample palaestra.

On the northeast side is the excavation for a large swimming tank, and for a water channel leading to the closet. In order to have water at hand for building purposes, the masons had built a low wall around an old impluvium on the south side into which a feed pipe ran.

For a short distance on the north side the stylobate had been made ready for the building of the colonnade; elsewhere only the preliminary work had been done.

The rooms at the southeast corner were no doubt intended for dressing rooms for the palaestra and the plunge bath.

Two small rooms open upon the north entrance of the palaestra; one of them, perhaps, was to be a ticket office, for the adjustment of matters relating to admission, the other a cloak room, in which the capsarius would guard the valuables of the bathers.

Two doors admit the visitor from the palaestra to the series of bath rooms, one of them opening from the north end of the colonnade.

The first room was designed to answer the purpose of a store, with four booths opening into it for the sale of edibles and bathers' conveniences. The apodyterium, tepidarium, and caldarium had each three large windows opening on the palaestra.

None of the rooms were finished, though a hollow floor and hollow walls had been built in the tepidarium, caldarium, and laconicum. Five smaller windows on the southeast side of the caldarium looked out on a narrow garden, about which the workmen had commenced to build a wall to cut off the sight of the firemen passing to and fro between the two furnaces.

The caldarium was so placed as to receive the greatest possible amount of sunlight, particularly in the afternoon hours, when it would be used; this was in accordance with a recommendation of Vitruvius, who says that the windows of baths ought, whenever possible, to face the southwest, otherwise the south.

The contrast is indeed marked between the numerous large windows here, with their attractive outlook, and the small apertures, high in the walls and ceiling, through which light was admitted in the older baths.

In the Central Baths there was no frigidarium; but a large basin for cold baths, nearly five feet deep, was placed in the dressing room opposite the windows. Supply pipes were so laid that jets would spring into the basin from three small niches, one in each wall.

The tepidarium—here, as usual, relatively small—is connected with the apodyterium by two doors, and similarly with the caldarium.

The latter room has a bath basin at each end, thus affording accommodations for twenty-six or twenty-eight bathers at once.

The hot air flues leading from the furnaces under the bath basins were already built, and above them openings were left for semi-cylindrical heaters like that in the women's caldarium of the Stabian Baths.

The round sweating room, laconicum, was made more ample by means of four semicircular niches, and lighted by three small round windows just above the cornice of the domed ceiling.

There was probably another round opening at the apex, designed for a bronze shutter, which could be opened or closed from below by means of a chain, so as to regulate the temperature. Doors led into the laconicum from both the tepidarium and the caldarium.

THE HOUSE OF THE VETTII/CASA DEI VETTI (#36)

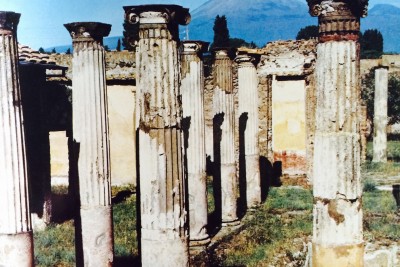

The house of the Vettii was situated in a quiet part of the city, and was not conspicuous by reason of its size. Its interest for us lies chiefly in its paintings and in the adornment of the well preserved peristyle.

The relationship between the two owners, Aulus Vettius Restitutus and Aulus Vettius Conviva is not known. They were perhaps freedmen, manumitted by the same master; Conviva, as we learn from a painted inscription, was a member of the Brotherhood of Augustus,—Vetti Conviva, Augustal[is].

Opening on the peristyle are three large apartments, and two smaller rooms. A door at the right leads into a small side peristyle, with a quiet dining room and bedroom. The domestic apartments were near the front of the house.

At the right of the principal atrium is a small side atrium without a separate street entrance. Grouped about it were rooms for the slaves and the kitchen with a large hearth. Beyond the kitchen is a room for the cook.

At the right of the principal atrium is a small side atrium without a separate street entrance. Grouped about it were rooms for the slaves and the kitchen with a large hearth. Beyond the kitchen is a room for the cook.

At the rear of the small atrium is the niche for the household gods. The columns of the peristyle are well preserved. They are white, with ornate capitals molded in stucco and painted with a variety of colors.

Part of the entablature also remains; the architrave is ornamented with an acanthus arabesque in white stucco relief on a yellow background. Nowhere else in Pompeii will the visitor so easily gain an impression of the aspect presented by a peristyle in ancient times. The main part of the house was searched for objects of value after the eruption, but the garden was left undisturbed, and we see in it today the fountain basins, statuettes, and other sculptures placed there by the proprietor.

Near the middle of the garden is a round, marble table. Three others stand under the colonnade, one of which, at the right near the inner end, is particularly elegant. The three feet are carved to represent lions' claws; the heads above are well executed, and there are traces of yellow color on the manes.

On two pillars in the garden are double busts, the subjects of which are taken from the bacchic cycle. One represents Bacchus and a bacchante, the other Bacchus and Ariadne; there are traces of painting on the hair, beard, and eyes.

The wall paintings of this house are the most remarkable discovered at Pompeii.

The earlier paintings are found in the atrium, the alae, and the large room at the end of the peristyle. The earlier paintings must have been placed upon the walls before the year 63, in the reign of Claudius or the earlier part of the reign of Nero.

The later pictures are on the walls of the fauces, the large apartment at the left of the atrium, the colonnade of the peristyle, the two dining rooms opening on the peristyle, and the small peristyle with the adjoining rooms; to the same class belongs also the painting of the Genius with the Lares in the side atrium, which, aside from this, contains no pictures.

The contrast between the earlier and the later decoration is so marked that it seems impossible to explain except on the assumption of a change of owners. We may well believe that about the middle of the first century this was the home of a family of culture and standing, who secured for the decoration of it the best artist that could be obtained, bringing him perhaps from Rome or from a Greek city.

But within a score of years afterwards the house passed into the hands of the Vettii, freedmen, perhaps, whose taste in matters of art was far inferior to that of the former occupants, and a number of rooms were redecorated.

STABIAN BATHS/TERME STABIANE (#40)

In comparison with the great bathing establishments of Rome, the baths at Pompeii are of moderate size. They have, however, a special interest, due in part to their excellent preservation, in part to the certainty with which the purpose of the various rooms can be determined; and their remains enable us to trace the development of the public bath in a single city during a period of almost two hundred years.

It is not easy for one living under present conditions to understand how important a place the baths occupied in the life of antiquity, particularly of the Romans under the Empire; they offered, within a single enclosure, opportunities for physical care and comfort and leisurely intercourse with others, not unlike those afforded in the cities of modern Europe by the club, the café, and the promenade.

Though the Roman baths differed greatly in size and in details of arrangement, the essential parts were everywhere the same. First there was a court, palaestra, surrounded by a colonnade.

This was devoted to gymnastic exercises, and connected with it in most cases was an open-air swimming tank. The dressing room, apodyterium, was usually entered from the court through a passageway or anteroom. A basin for cold baths was sometimes placed in the dressing room; in large establishments a separate apartment was set aside for this purpose, the frigidarium.

To avoid too sudden a change of temperature for the bathers, a room moderately heated, tepidarium, was placed between the dressing room and the caldarium, in which hot baths were given.

To avoid too sudden a change of temperature for the bathers, a room moderately heated, tepidarium, was placed between the dressing room and the caldarium, in which hot baths were given.

At one end of the caldarium was a bath basin of masonry, alveus; at the other was ordinarily a semicircular niche, schola, in which stood the labrum, a large, shallow, circular vessel resting upon a support of masonry, and supplied with lukewarm water by a pipe leading from a tank back of the furnace.

The more extensive establishments, as the Central Baths at Pompeii, contained also a round room, called laconicum from its Spartan origin, for sweating baths in dry air. In describing baths it is more convenient to use the ancient names.

In earlier times the rooms were heated by means of braziers, and in one of the Pompeian baths the tepidarium was warmed in this way to the last.

A more satisfactory method was devised near the beginning of the first century B.C. by Sergius Orata, a famous epicure, whose surname is said to have been given to him because of his fondness for golden trout (auratae). He was the inventor of the 'hanging baths’, or balneae pensiles.

These were built with a hollow space under the floor, the space being secured by making the floor of tiles, two feet square, supported at the corners by small brick pillars; into this space hot air was introduced from the furnace, and as the floor became warm, the temperature of the room above was evenly modified.

This improved method of heating was not long restricted to the floors. As early as the Republican period, the hollow space was extended to the walls by means of small quadrangular flues and by the use of nipple tiles, tegulae mammatae, large rectangular tiles with conical projections at each corner. In bathing establishments designed for both men and women, the two caldaria were placed near together.

There was a single furnace, hypocausis, where the water for the baths was warmed; from this also hot air was conveyed through broad flues under the floors of both caldaria, thence circulating through the walls. Through similar flues underneath, the warm air, already considerably cooled, was conveyed from the hollow spaces of the caldaria into those of the tepidaria.

In order to maintain a draft strong enough to draw the hot air from the furnace under the floors, the air spaces of the walls had vents above, remains of which may still be seen in some baths. In order to warm them at the outset a draft fire was needed,—that is, a small fire under the floor at some point a considerable distance from the furnace and near the vents, through which it would cause the escape of warm air, and so start a hot current from the furnace.

The place of the draft fire has been found under two rooms of the Pompeian baths. The most common form of the bath was that taken after exercise in the palaestra,—ball playing was a favorite means of exercise,—use being made of all the rooms. The bather undressed in the apodyterium, or perhaps in the tepidarium, where he was rubbed with unguents; then he took a sweat in the caldarium, following it with a warm bath.

Returning to the apodyterium, he gave himself a cold bath either in this room or in the frigidarium; he then passed into the Laconicum, or, if there was no Laconicum, went back into the caldarium for a second sweat; lastly, before going out, he was thoroughly rubbed with unguents, as a safeguard against taking cold. Some bathers omitted the warm bath.

They passed through the tepidarium directly into the laconicum or caldarium, where they had a sweat; they then took a cold bath, or had cold water poured over them, and were rubbed with unguents. In the simplest form of the bath the main rooms were not used at all.

The bathers heated themselves with exercise in the palaestra, then removed the dirt and oil with scrapers and bathed in the swimming tank. The largest and oldest bathing establishment at Pompeii is that to which the name Stabian Baths has been given, from its location on Stabian Street.

It was built in the second century B.C., but was remodelled in the early days of the Roman colony, and afterwards underwent extensive repairs. It is of irregular shape, and occupies a large part of a block.

Entering from the south through the broad doorway, we find ourselves in the palaestra, which has a colonnade on three sides.

On the east side of the court are the men's baths, rooms; north of these are the women's baths, with the furnace room between them.

The anteroom of the men's baths, opens at one end into the dressing room or apodyterium. It has a vaulted ceiling, richly decorated.

A door at the left leads into the frigidarium, and another at the right into a servants' waiting room.

The apodyterium also was provided with benches of the same sort.

Along the walls at the sides, just under the edge of the vaulted ceiling, was a row of small niches, the use of which corresponded with that of the lockers in a modern gymnasium.

More effective is the decoration of the small round frigidarium. Light is admitted, as in the Pantheon at Rome, through a round hole in the apex of the domed ceiling.

At the edge of the circular bath basin, lined with white marble, was a narrow strip of marble floor, which is extended into the four semicircular niches. Wall and niches alike are painted to represent a beautiful garden, with a blue sky above.

The tepidarium and caldarium were heated by means of hollow floors and walls. The former is much the smaller, as we should have expected from its use as an intermediate room, in which the bathers would ordinarily not tarry so long as in the caldarium.

The women's baths are entered from the court through a long anteroom; the dressing room is connected also with the two side streets by means of corridors.

The apodyterium is the best preserved room of the entire building, and also the most ancient. It shows almost no traces of the catastrophe.

The vaulted ceiling is intact. The smooth, white stucco on the walls and the simple cornice at the base of the lunettes date from the time of the first builders. Now, as then, light is admitted only through two small openings in the crown of the vault and a window in the west lunette.

The women had no frigidarium. A large basin for cold baths was built at the west end of the dressing room, but this also is a later addition; before it was made, those who wished for cold baths must have contented themselves with portable bath tubs.

The tepidarium and caldarium are in a better state of preservation than those of the men's baths, which they closely resemble.

FORUM TRIANGULARE & DORIC TEMPLE/ FORO TRIANGOLARE & TEMPIO DORICO (#41 & 42)

The end of the old lava stream on which Pompeii lay runs off into two points; in the depression between them, was the Stabian Gate.

On the edge of the spur at the left a temple of the Doric style was built in very early times.

The sides of the temple followed in general the direction of the edge of the cliff. In the second century B.C. the northwest corner of the depression back of the Stabian Gate was selected as the site for a large theater.

This location was chosen, in accordance with the Greek custom.

The architect, if not a Greek, was certainly of Greek training. South of the theater an extensive colonnade was erected.

It was intended as a shelter for theater-goers, but was afterwards turned into barracks for gladiators.

With a similar purpose, a colonnade of the Doric order was built along two sides of the triangular level space about the Greek temple.

In front of the north end, where the two arms of the colonnade meet, a high portico of the Ionic order was erected facing the street, thus forming a monumental entrance to the Theater.

The southwest side of the area was left unobstructed, and the place, by reason of its shape, is called the Forum Triangulare, 'Three-cornered Forum.' Early in the Roman Period, not long after 80 B.C., a small roofed theater was constructed east of the stage of the Large Theater and of the area at the rear. Stabian Street north and south of the Small Theater was lined with private houses.

At the northeast corner of the block was a temple of Zeus Milichius, seemingly of early date, but entirely rebuilt about the time that the Small Theater was erected.

Of the ancient Doric temple little remains: only the foundation, which was high for a Greek temple, with a flight of steps in front; two stumps of columns and traces of a third; four capitals, and portions of the right wall of the cella.

Of the ancient Doric temple little remains: only the foundation, which was high for a Greek temple, with a flight of steps in front; two stumps of columns and traces of a third; four capitals, and portions of the right wall of the cella.

The temple was of mixed construction, part stone and part wood. In respect to age this temple must have been built in the 6th century B.C. At the time of the eruption the temple was in ruins.

LARGE THEATER/TEATRO GRANDE (#43)

Performances upon the stage were first given in Rome in the year 364 B.C.; a pestilence was raging, and the Romans thought to appease the gods by a new kind of celebration in their honor.

The performers were brought from Etruria, and the exercises were limited to dancing, with an accompaniment on the flute.

There was as yet no Latin drama. The first regular play was presented more than a century later, in 240B.C., and the playwright was not a Roman but a Greek from Tarentum, Livius Andronicus, who translated both tragedies and comedies from his native tongue.

The first stone theater in Rome was built by Pompey, the rival of Caesar, in 55 B.C.

In Pompeii, on the contrary, a permanent theater had been erected at least a hundred years earlier. The Oscan culture was so completely merged in that of Rome that our knowledge of it as an independent development is extremely slight.

From literary sources we know only of a crude form of popular comedy in which, as in the Italian Commedia dell' arte, there were stock characters distinguished by their masks,—Maccus a buffoon, Bucco a voracious, talkative lout, Pappus an old man who is always cheated, and Dossennus a knave. The scene of these exhibitions was always Atella, the Gotham of Campania, whence they were called Atellan farces.

From literary sources we know only of a crude form of popular comedy in which, as in the Italian Commedia dell' arte, there were stock characters distinguished by their masks,—Maccus a buffoon, Bucco a voracious, talkative lout, Pappus an old man who is always cheated, and Dossennus a knave. The scene of these exhibitions was always Atella, the Gotham of Campania, whence they were called Atellan farces.

The Theater at Pompeii, however, is a proof that as early as the second century B.C., in at least one Campanian city, dramatic representations of a high order were given.

Here, perhaps, as at Athens, they were associated with the worship of Dionysus; for the satyrs were companions of the Wine-god, and the head of a satyr, carved in tufa, still projects from the keystone of the arch at the outer end of one of the vaulted passages leading to the orchestra.

Greek verse, and native verse modelled after the Greek, must have gained a hearing at Pompeii, and the works of Oscan poets—not a line of which has come down to us—must have stirred the hearts of the people long before Livius Andronicus, and Naevius, who brought inspiration from his Campanian home, produced their dramas at Rome.

The cavea, the large outer part containing seats for spectators afforded seats for about five thousand persons. The seats are arranged in three semicircular sections. The lowest, ima cavea, next to the orchestra, contains four broad ledges on which, as well as in the orchestra itself, the members of the city council, the decurions, could place their chairs, the 'seats of double width.' The middle section, media cavea, was much deeper, extending from the ima cavea to the vaulted corridor. It contained twenty rows of marble seats arranged like steps, of which only a small portion is preserved. On a part of one of these, individual places, a little less than 16 inches wide, are marked off by vertical lines in front, and numbered.

In Rome the fourteen rows nearest the bottom were reserved for the knights. Whether a similar arrangement prevailed in the municipalities and the colonies is not known, but if so the number reserved here must have been smaller.

The upper section, summa cavea, supported by the vault over the corridor, was too narrow to have contained more than four rows of seats.

The ima cavea was entered from the orchestra. The media cavea could be entered on the lower side from the passage (diazoma, praecinctio) between it and the ima cavea, which at the ends was connected by short flights of steps with the parodoi leading outside; on the upper side six doors opened into the media cavea from the corridor, from which flights of steps descended dividing the seats into five wedge-like blocks, cunei, with a small oblong block in addition on either side near the end of the stage.

The summa cavea, which for convenience we may call the gallery, was entered by several doors from a narrow vaulted passage along the outside. The outer wall back of the gallery rose to a considerable height above the last row of seats.

On the inside near the top were projecting blocks of basalt, containing round holes in which strong wooden masts were set; from these the great awning, velum, was stretched over the cavea and orchestra to the roof of the stage, protecting the spectators from the sun.

This sort of covering for the theater was a Campanian invention, and here, where the cavea opened toward the south, was especially necessary. The stage is long and narrow, measuring 120 by 24 Oscan feet; the floor is a little more than three feet above the level of the orchestra.

The rear wall, as in ancient theaters generally, was built to represent the front of a palace, entered by three doors, and adorned with columns and niches for statues. In each of the short sections of wall at the ends of the stage is a broad doorway, extending across almost the entire space.

The long narrow room behind the stage, used as a dressing room (postscaenium), was entered by a door at the rear, which was reached by an inclined approach.

No trace of the roof of the stage remains, but from the better preserved theaters at Orange, in the south of France, and at Aspendus, in Asia Minor, we infer that it sloped back toward the rear wall. The floor was of wood.

The theater in antiquity was by no means reserved for scenic representations alone. It was a convenient place for bringing the people together, and was used for public gatherings of the most varied character. In the theater at Tarentum the memorable assembly met which heaped insults upon the Roman ambassadors and precipitated war with Rome.

Our Theater, as is evident from the character of the construction, in its original form belonged to the Tufa Period, but was rebuilt in Roman times. Some particulars in regard to the rebuilding are given in an inscription: M. M. Holconii Rufus et Celer cryptam, tribunalia, theatrum,—'Marcus Holconius Rufus and Marcus Holconius Celer (built) the crypt, the tribunals, and the part designed for spectators,' that is, the vaulted corridor under the gallery, the platforms over the entrances to the orchestra, and the cavea. The two Holconii lived in the time of Augustus. The elder, Rufus, was duumvir for the 4th term in 3-2 B.C.

The work on the Theater was probably done about that time; for soon afterwards, before his 5th duumvirate, a statue in his honor was erected in the Theater, as we learn from an inscription. Later, in 13-14 A.D., the younger Holconius also, when he had been chosen quinquennial duumvir, was honored with a statue.

The architect employed by the Holconii, a freedman, was not honored with a statue, but his name was transmitted to posterity in an inscription placed in the outer wall near the east entrance to the orchestra: M. Artorius M. l[ibertus] Primus, architectus,—'Marcus Artorius Primus, freedman of Marcus, architect.'

The plan of the Theater conforms to the Greek type. In the Roman theater the orchestra was in the form of a semicircle, of which the diameter was represented by the stage. In Greek theaters, on the contrary, the stage according to Vitruvius was laid out on one side of a square inscribed in the circle of the orchestra; the orchestra, as shown by existing remains, in most cases was either a complete circle or was so extended by tangents at the sides that a circle could be inscribed in it.

The latter is the case in our Theater, of which the orchestra has essentially the same form as that of the theater of Dionysus at Athens.

SMALL THEATER/TEATRO PICCOLO (#45)

The names of the builders of the Small Theater are known from an inscription which is found in duplicate in different parts of the building: C. Quinctius C. f. Valg[us], M. Porcius M. f. duovir[i] dec[urionum] decr[eto] theatrum tectum fac[iundum] locar[unt] eidemq[ue] prob[arunt],—'Gaius Quinctius Valgus the son of Gaius and Marcus Porcius the son of Marcus, duumvirs, in accordance with a decree of the city council let the contract for building the covered theater, and approved the work.'

Later the same officials, when, after the customary interval, they had been elected quinquennial duumvirs, built the Amphitheater 'at their own expense'. The seating capacity of the building was about fifteen hundred.

The lowest section of the cavea, as in the Large Theater, consisted of four low, broad ledges on which the chairs of the decurions could be placed.

The pavement of the orchestra consists of small flags of colored marble.

An inscription in bronze letters informs us that it was laid by the duumvir Marcus Oculatius Verus pro ludis, that is instead of the games which he would otherwise have been expected to provide.

TEMPLE OF ASCHLEPIUS OR ZEUS MILICHIUS/TEMPIO DI ASCLEPIO O DI GIOVE MELICHIO (#46)

The small temple near the northeast corner of the block containing the theaters is entered from Stabian Street.

The court, like that of the temple of Vespasian, has a colonnade across the front; only the foundation and a Doric capital of lava are preserved.

At the end of the colonnade on the right is the room of the sacristan.

The large altar stands close to the foot of the steps leading up to the temple. It is built of blocks of tufa, with a frieze of triglyphs and panels like those found on walls in the first style of decoration.

The steps extend across the front of the temple, the unusual elevation of which is explained by the inequality of the ground.

Of the six columns in the tetrastyle portico no remains have been found, but three capitals of pilasters are preserved, two belonging to those at the corners of the cella, and one, considerably smaller, to a doorpost; they are of tufa, and were once covered with white stucco.

Of the six columns in the tetrastyle portico no remains have been found, but three capitals of pilasters are preserved, two belonging to those at the corners of the cella, and one, considerably smaller, to a doorpost; they are of tufa, and were once covered with white stucco.

The excellent proportions and fine workmanship of the capitals point to the period of the first style of decoration; there was formerly a remnant of that style on the north wall of the cella, copied before 1837.

Nevertheless the quasi-reticulate masonry of the cella, closely resembling that of the Small Theater, dates from the early years of the Roman colony. In this period the temple in its present form was built, perhaps with the help of native Pompeian masons.

Attached to the rear wall of the cella was an oblong pedestal on which were placed two statues, representing Jupiter and Juno, together with a bust of Minerva, all of terra cotta and of poor workmanship.

The suggestion at once presents itself that this was the Capitolium, erected by the Roman colonists soon after they settled in Pompeii.

We should probably recognize in the head carved on the smallest of the pilaster capitals a representation of Zeus Milichius, a divinity honored in many parts of Greece, especially by the farmers; Zeus the Gracious, the patron of tillers of the soil.

The serious, kindly face, bearded and with long locks, was more than a mere ornament; it was the god himself looking down upon the worshipper who entered his sanctuary.

For printing our entire Pompeii Guide (facing pages) you can download the PDF by clicking HERE

For offline reading on your smartphone or tablet, you can download the PDF of our entire Pompeii Guide (single page) by clicking HERE

If you have an Android OS, you will find it in your Download app.

If you have an iPhone or an iPad, open and save it in iBook (free app).