Our Suggested Guide of Pompeii, Part 2

Amalfi Coasting selected excerpts from “POMPEII: ITS LIFE AND ART”, by German archeologist August Mau, which is considered one of the best books ever written about Pompeii in terms of historical narrative and archeological facts and explanation. This is Part 2 of our excerpts.

BUILDINGS AT THE NORTHWEST CORNER OF THE FORUM, AND THE TABLE OF STANDARD MEASURES

The large building at the northwest corner of the Forum was erected after the earthquake of the year 63. It is divided into three parts.

Below, at the level of the Forum, are two dark vaulted chambers, one at the rear of the other. It has been supposed, not without probability, that these were the vaults of the city treasury, the aerarium.

Above these chambers are two rooms which, if the identification of the chambers below as the vaults of the city treasury is correct, must have been occupied by the treasury officials. The last of the three parts of the building is by far the largest.

It was a high and spacious hall, with numerous entrances from the Forum. It was divided into two rooms by two short sections of wall projecting from the sides, and was evidently a market house, perhaps for vegetables and farm products. The rooms formed by enclosing the small colonnade at the rear of the court of Apollo have already been mentioned.

At the left of the stairway leading to the second story is a small room which opens in its entire breadth upon the Forum.

Close by is a recess, also open toward the Forum. In this recess stood the table of standard measures, mensa ponderaria, which is now in the Naples Museum. It is a large slab of limestone (a little over 8 feet long and 1.8 wide), in which are nine bowl-shaped cavities with holes at the bottom through which the contents could be drawn off; this slab rested on two stone supports, and similar supports above it carried another slab, which is now lost, with three cavities.

The table thus contained twelve standards of capacity for liquid and dry measure, but only ten are shown in the illustration, as two are too far back. It is evident that the table has come down from the pre-Roman period.

The names of the measures were originally written in Oscan, beside the five largest cavities, and though the letters were later erased, they are still in part legible. Only one word, however, can be made out with certainty, beside the next to the smallest cavity; that is Kuiniks, plainly the same as the Greek Choinix. We naturally infer that in the pre-Roman time the Pompeians used Greek measures.

In the time of Augustus, about 20 B.C., the cavities were enlarged and made to conform to the Roman standard. The adoption of a uniform standard was made a subject of imperial regulation by Augustus, who, by this means, sought to promote the unification of the Empire.

Similar tables of measures have been found in various parts of the Roman world, as at Selinunte in Sicily, in the Greek islands, and at Bregenz on the Lake of Constance.

TEMPLE OF VENUS POMPEIANA/TEMPIO DI VENERE (#3 on the map)

For some years it had been known that a temple once stood in the rectangular block south of the Strada della Marina; and in 1898 workmen excavating here began to uncover the massive foundations.

When the volcanic deposits had been removed it was seen that the court of the temple, with the surrounding colonnade, occupied the whole area between the Basilica and the west wall of the long room now used as a Museum.

On the podium was found a part of a statuette of Venus, of the familiar type which represents the goddess as preparing to enter the bath; it was probably a votive offering set up by some worshipper.

In the subterranean passageway entered near the southeast corner the excavators found another votive offering, a bronze steering paddle of the kind shown in paintings as an attribute of Venus Pompeiana.

From these indications, as well as from the size of the temple and its location, near the Forum and on an elevation commanding a wide view of the sea, we are safe in assigning the sanctuary to Venus Pompeiana, the patron divinity of Roman Pompeii.

Prior to the founding of the Roman colony the site of the temple had been occupied by houses, built in several stories on the edge of the hill. In less than a century and a half the temple was twice built, twice destroyed; a third building was in progress at the time of the eruption.

The first temple was erected in the early years of the Roman colony. An area approximately 185 Roman feet square was prepared for it by levelling off and filling up, terrace walls being built to hold in place the earth and rubbish used for filling.

In front of the temple are remains of a large altar of whitish limestone. On the east side of the court is the base of an equestrian statue, of the same material, which was afterwards veneered with marble; near it is a pedestal of a standing figure, of masonry covered with stucco, and behind this is the small base of a fountain figure.

After the completion of the temple the Pompeians set about rebuilding the colonnade, on a scale of equal magnificence.

How far the work had progressed before the earthquake of the year 63 it is not easy to determine. Not less than three hundred marble columns must have been required to complete the work.

In point of size, the temple with its court formed the largest sanctuary, in richness of materials the most splendid edifice of the entire city. The great earthquake felled to the ground alike the finished temple and the unfinished colonnade.

But the Pompeians soon commenced the work of rebuilding.

The third temple was to be even more imposing than its predecessor. The old steps were removed from the front.

The existing podium was cut back five Roman feet on each side, and four inches at the rear, to form the core of the new podium; on all sides of this a massive foundation wall was commenced, five and a half Roman feet thick, made of large blocks of basalt carefully worked and fitted.

At the time of the eruption five courses of basalt had been laid, reaching a height of more than four.

TEMPLE OF APOLLO/ TEMPIO DI APOLLO (#4)

The building had been completely restored after the earthquake of 63, and was in good order at the time of its destruction.

Though ancient excavators removed many objects of value, including the statue of the divinity of the temple, much was left undisturbed, as the interesting series of statues in the court; in addition, a number of inscriptions have been recovered.

On the whole, more complete information is at hand regarding this sanctuary than in reference to any other in Pompeii.

The temple stood upon a high podium, in front of which is a broad flight of steps.

The small cella was evidently intended for but one statue.

The columns at the sides of the deep portico, which in other respects follows the Etruscan plan, are continued in a colonnade which is carried completely around the cella. It presents an odd mixture of styles, of which other examples also are found at Pompeii; a Doric entablature with triglyphs was placed upon Ionic columns having the four-sided capital known as Roman Ionic.

The second story was probably of the Corinthian order.

The pedestal in the cella, on which the statue of Apollo stood, still remains, but no trace of the statue itself has been found.

Other divinities besides Apollo were honored in this sanctuary, which in the earlier time was evidently the most important in the city; statues and altars for their worship were placed in the court.

The statues themselves, with one exception, have been taken to Naples. There were in all six of them, grouped in three related pairs.

In front of the third column at the left of the entrance, stood Venus, at the right was a hermaphrodite—both marble figures of about one half life size.

They belong to the pre-Roman period and were originally of good workmanship, but even in antiquity they had been repeatedly restored and worked over. As a work of art, the hermaphrodite is the more important.

BASILICA (#5 )

The Basilica, at the southwest corner of the Forum, was the most magnificent and architecturally the most interesting building at Pompeii.

Its construction and decoration point to the pre-Roman time; and there is also an inscription scratched on the stucco of the wall, dating from almost the beginning of the Roman colony: C. Pumidius Dipilus heic fuit a. d. v. nonas Octobreis M. Lepid. Q. Catul. cos.,—'C. Pumidius Dipilus was here on the fifth day before the nones of October in the consulship of Marcus Lepidus and Quintus Catulus,' that is October 3, 78 B.C.

The name basilica (basilike stoa, 'the royal hall') points to a Greek origin; we should naturally look for the prototype of the Roman as well as the Pompeian structure in the capitals of the Alexandrian period and in the Greek colonies of Italy.

A basilica was a spacious hall which served as an extension of a market place, and was itself in a certain sense a covered market. It was not limited to a specific purpose; in general, whatever took place on the market square might take place in the basilica, the roof of which afforded protection against the weather.

It was chiefly devoted, however, to business transactions and to the administration of justice.

The main hall and the corridor were devoted to trade; the dealers perhaps occupied the former, while in the latter the throng of purchasers and idlers moved freely about.

The place set aside for the administration of justice, the tribunal, was ordinarily an apse projecting from the rear end. In our Basilica, however,—and in some others as well,—it was a small oblong elevated room back of the central hall, toward which it opened in its whole length.

The Pompeians, who at the time when it was built were pupils of the Greeks in matters of art, found their model not in Rome but in a Greek city, perhaps Naples. Five entrances, separated by tufa pillars, lead from the colonnade of the Forum into the east end of the basilica.

There are only scanty remains of the floor, which consisted of bits of brick and tile mixed with fine mortar and pounded down (opus Signinum); it extended in a single level over the whole enclosed space, and from this level our estimates of height are reckoned.

The large columns about the main hall, with a diameter of more than 3½ feet, must have been at least 32 or 33 feet high; the attached half-columns with the columns at the entrance and at the rear, including the Ionic capitals, were probably not more than 20 feet high.

The tribunal at the rear is the most prominent and architecturally the most effective portion of the building.

The base is treated in a bold, simple manner; upon it, at the front, stands a row of columns the lower portions of which show traces of latticework. The decoration of the walls, like that of the rest of the interior, imitates a veneering of colored marbles.

The shape and comparatively narrow dimensions of the elevated room indicate that we have here a tribunal in the strict sense, a raised platform for the judge and his assistants. Here the litigants stood on the floor in front of the tribunal, and when court was in session the general public must have been excluded from this part of the corridor.

Under the tribunal was a vaulted chamber half below the level of the ground; two round holes, indicated on the plan, opened into it from above. It could hardly have been designed as a place for the confinement of prisoners; escape would have been easy by means of two windows in the rear, especially when help was rendered from the outside.

More likely it was used, in connection with the business of the court, as a storeroom, in which writing materials and the like, or even documents, might be kept; they could easily have been passed up through the holes when needed.

FORUM (#6 )

The Forum is usually approached from the west side by the short, steep street leading from the Porta Marina.

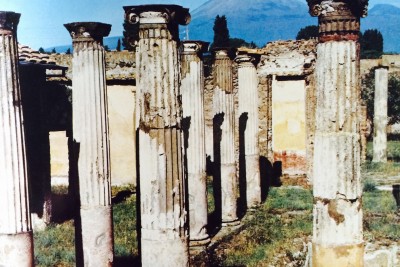

Entering, we find ourselves near the lower end of an oblong open space, at the upper end of which, toward Vesuvius, stands a high platform of masonry with the ruins of a temple—the temple of Jupiter; the remains of a colonnade are seen on each of the other three sides.

Including the colonnade the Forum measures approximately 497 feet in length by 156 in breadth; without it the dimensions are 467 and 126 feet.

The north side, at the left of the temple, is enclosed by a wall in which there are two openings, one at the end of the colonnade, the other between this and the temple; at the right the wall bounding the open space has been replaced by a stately commemorative arch, while the end of the colonnade is closed by a wall with a passageway.

Another arch, of much simpler construction, stands at the left of the temple, in line with the façade; it cuts off the area between the temple and the colonnade from the rest of the Forum. A third arch once stood in a corresponding position at the right.

No private houses opened on this area; it was wholly given up to the public life of the city and was surrounded by temples, markets, and buildings devoted to the civic administration. The area of the Forum was paved with rectangular flags of whitish limestone.

In front of the colonnade, the pavement of which was about twenty inches above that of the open space, a broad step or ledge projected, covering a gutter for rain water; the water found its way into the gutter through semicircular openings in the outer edge of the step.

Of the many statues that once adorned the Forum not one has been found. As may be seen from the pedestals still in place, they were of three kinds, and varied greatly in size.

First, statues of citizens who had rendered distinguished services were placed in front of the colonnade on the ledge over the gutter.

Four pedestals that once supported statues of this sort may be seen on the west side.

Then equestrian statues of life size were set up in front of the ledge, these also in honor of dignitaries of the city. On one of the pedestals the veneering of colored marble is still preserved, with an inscription showing that the person represented was Quintus Sallustius, "Duumvir, Quinquennial Duumvir, Patron of the Colony."

Finally, on the south side, the life size equestrian statues were almost all removed in order to make room for four much larger statues, the pedestals of which still remain.

These must have represented emperors, or members of the imperial families.

The pedestal in the middle is the oldest. Upon it was probably placed a colossal statue of Augustus.

Near the southeast corner an inscription was found: V[ibius] Popidius Ep[idii] f[ilius] q[uaestor] porticus faciendas coeravit, 'Vibius Popidius, the son of Epidius, when quaestor caused this colonnade to be erected.'

No clew to the date is given, but it must have been before the coming of the Roman colony, for after that time there was no office of quaestor in Pompeii. It must also have been before the Social War. We may with much probability assign the inscription to the second half of the second century B.C.

Remains of the colonnade of Popidius are still to be seen on the south side, and on the adjoining part of the east side, extending just across Abbondanza Street.

The Basilica at the southwest corner and the temple of Jupiter both conform to the same variation from the direction of the early north and south street that we have noticed in the case of the colonnade of Popidius; they belong, therefore, to the same remodelling of the Forum.

It is quite possible that the erection of the temple, by limiting the area of the Forum on the north side, caused its extension toward the south beyond the earlier boundary.

A remodelling of the Forum commenced in the early years of the Empire, the pavement having been laid before the pedestal of the monument to Augustus was built. It was never carried to completion.

On the west side the new colonnade was almost finished when the earthquake of the year 63 threw it nearly all down.

At the time of the eruption only the columns at the south end of this side, which had safely passed through the earthquake, were still standing with their entablature.

The area was then strewn with blocks, which the stonecutters were engaged in making ready for the rebuilding. The Forum of Pompeii, as of other ancient cities, was first of all a market place.

Early in the morning the country folk gathered here with the products of the farm; here all day long tradespeople of every sort exhibited their wares.

In later times the pressure of business led to the erection of separate buildings around the Forum to relieve the congestion; such were the Macellum, used as a provision market; the Eumachia building, erected to accommodate the clothing trade; the Basilica and the market house west of the temple of Jupiter, devoted to other branches of trade.

Yet in a literal sense the Forum always remained the business center of the city. It served, too, as the favorite promenade and lounging place, where men met to discuss matters of mutual interest.

The life of the Forum seemed so interesting to one of the citizens of Pompeii that he devoted to the portrayal of it a series of paintings on the walls of a room.

The pictures give a vivid representation of ancient life in a small city. First, in front of the equestrian statues near the colonnade we see dealers of every kind and description. There sits a seller of copper vessels and iron utensils. Next come two shoemakers, one waiting on women, another on men; then two cloth dealers. Further on a man is selling portions of warm food from a kettle; then we see a woman with fruit and vegetables, and a man selling bread. Another dealer in utensils is engaged in eager bargaining, while his son, squatting on the ground, mends a pot. Then come men wearing tunics, engaged in some transaction. Beyond these, some men are taking a walk; a woman is giving alms to a beggar; and two children play hide and seek around a column.

The following scene is not easy to understand, but apparently has reference to some legal process; a woman leads a little girl with a small tablet before her breast into the presence of two seated men who wear the toga.

The most important religious festivals were celebrated in the Forum. Here naturally festal honors were paid to the highest of the gods—the whole area enclosed by the colonnade was the court of his temple; but we learn from an inscription, mentioned below, that celebrations were held here in honor of Apollo also, whose temple adjoined the Forum, and was at first even more closely connected with it than in later times.

Vitruvius informs us that in Greek towns the market place, agora, was laid out in the form of a square (a statement which is not confirmed by modern excavations), but that in the cities of Italy, on account of the gladiatorial combats, the Forum should have an oblong shape, the breadth being two thirds of the length.

The purpose in giving a lengthened form to the Forum, as also to the Amphitheater, was no doubt to secure, at the middle of the sides, a greater number of good seats, from which a spectacle could be witnessed.

In the Pompeian Forum the breadth is less than one third of the length. However, there can be little doubt that gladiatorial exhibitions were frequently held there before the building of the Amphitheater, which dates from the earlier years of the Roman colony. After this time the Forum was still used for games and contests of a less dangerous character.

MUNICIPAL BUILDINGS/EDIFICI AMMINISTRAZIONE PUBBLICA (#7)

At the south end of the Forum were three buildings similar in plan and closely connected. The building at the right was at the corner of the Forum, while the space separating the other two lay on a line dividing the Forum into two equal parts; east of the last building is the Strada delle Scuole.

The three buildings were erected after the earthquake of 63, on the site of older buildings of the same character.

In the walls of that furthest east, considerable remains of the earlier walls are embodied; in that near the corner the original pavement is preserved, and in the middle building there are traces of the original pavement.

These spacious halls must have served the purposes of the city administration.

The two at the right and the left are alike in having at the end opposite the entrance an apse large enough to accommodate one or more magistrates with their attendants; they were the official quarters of the aediles and the duumvirs, while the middle hall was the council chamber, curia, where the decurions met.

The middle room was obviously intended to be the most richly ornamented of the three, and was further distinguished from the others by the elevation of its floor, which was more than two feet above the pavement of the colonnade.

In front of the entrance is a platform reached at either end by an approach hardly wide enough for two persons, thus suited for a select rather than a large attendance.

The office of the aediles, situated at the corner of the colonnade and close to the Basilica was particularly convenient for magistrates who, among other duties, were charged with the maintenance of order and the enforcement of regulations in the markets.

BUILDING OF EUMACHIA/EDIFICIO DI EUMACHIA (#8 )

The plan of the large building on the east side of the Forum, between the temple of Vespasian and Abbondanza Street, is simple and regular. In front is a deep portico, facing the Forum.

The interior consists of a large oblong court with three apses at the rear and a colonnade about the four sides; on three sides there is a corridor behind the colonnade, with numerous windows opening upon.

An inscription appears in large letters on the entablature of the portico, and again on a marble tablet over the side entrance in Abbondanza Street: Eumachia L. f., sacerd[os] publ[ica], nomine suo et M. Numistri Frontonis fili chalcidicum, cryptam, porticus Concordiae Augustae Pietati sua pequnia fecit eademque dedicavit,—'Eumachia, daughter of Lucius Eumachius, a city priestess, in her own name and that of her son, Marcus Numistrius Fronto, built at her own expense the portico, the corridor (cryptam, covered passage), and the colonnade, dedicating them to Concordia Augusta and Pietas.’

The word pietas, in such connections, is difficult to translate. It sums up in a single concept the qualities of filial affection, conscientious devotion, and obedience to duty which in the Roman view characterized the proper conduct of children toward their parents and grandparents. Here mother and son united in dedicating the building to personifications, or deifications, of the perfect harmony and the regard for elders that prevailed in the imperial family.

The word pietas, in such connections, is difficult to translate. It sums up in a single concept the qualities of filial affection, conscientious devotion, and obedience to duty which in the Roman view characterized the proper conduct of children toward their parents and grandparents. Here mother and son united in dedicating the building to personifications, or deifications, of the perfect harmony and the regard for elders that prevailed in the imperial family.

The reference of the dedication can only be to the relation between the Emperor Tiberius and his mother Livia. In 22 A.D., when Livia was very ill, the Senate voted to erect an altar to Pietas Augusta.

In the following year Drusus, the son of Tiberius, gave expression to his regard for his grandmother by placing her likeness upon his coins, with the word Pietas. At the time of the eruption men were still engaged in rebuilding the parts of the edifice that had suffered in the earthquake of 63.

The front wall at the rear of the portico was finished and had received its veneering of marble; as shown by the existing remains, it conformed to the plan of the earlier structure.

The columns and entablature of the portico had not yet been set in place; considerable portions of them were found in the area of the Forum.

In front of the entrance from Abbondanza Street, is a fountain of the ordinary Pompeian form; as the material is limestone it is probably of later date than the other fountains, which are generally of basalt.

The figure represents Concordia Augusta, but the name Abundantia, given to it when first discovered, still lingers in the Italian name for the street, which might more appropriately have been called Strada della Concordia.

TEMPLE OF VESPASIAN/TEMPIO DI VESPASIANO (#9 )

South of the sanctuary of the City Lares is another religious edifice of an entirely different character.

Passing from the Forum across the open space once occupied by the portico—of which no remains have been found—we enter a wide doorway and find ourselves in a four-sided court somewhat irregular in shape.

The front part is occupied by a colonnade. At the rear a small temple stands upon a high podium which projects in front of the cella and reached by two flights of steps.

The front part is occupied by a colonnade. At the rear a small temple stands upon a high podium which projects in front of the cella and reached by two flights of steps.

The pedestal for the image of the divinity is built against the rear wall. In the middle of the court is an altar faced with marble and adorned on all four sides with reliefs of moderately good workmanship.

The temple itself was built, together with the court, after the earthquake of 63, and at the time of the eruption the work was not entirely completed.

The walls of the cella and of the entrance from the Forum had received their veneering of marble and were in a finished state; but those of the court were still awaiting completion.

The temple must have been built in the time of Vespasian, who reigned from 68 to 79 A.D.; and as this emperor possessed too great simplicity of character to allow men to worship him as a god while he was still alive, it was probably dedicated to his Genius.

SANCTUARY OF THE CITY LARES/SANTUARIO DEI LARI PUBBLICI (#10)

In earlier times a street opened into the Forum south of the macellum.

Later, apparently in the time of Augustus, it was closed, and the end, together with adjoining space at the south, was occupied by a building which measures approximately sixty by seventy Roman feet. In richness of material and architectural detail this was among the finest edifices at Pompeii. Its walls and floors were completely covered with marble.

It is evident that we have here a place of worship, yet not, properly speaking, a temple.

It is evident that we have here a place of worship, yet not, properly speaking, a temple.

The shrine in the apse, with its broad pedestal for several relatively small images, presents a striking analogy to the shrines of the Lares found in so many private houses.

Cities, as well as households, had their guardian spirits. The worship of these tutelary divinities was reorganized by Augustus, who ordered that, just as the Genius of the master of the house was worshipped at the family shrine, so his Genius should receive honor together with the Lares of the different cities.

As the house had its shrine for the Lares, so also had the city. Undoubtedly we should recognize in this edifice the sanctuary of the Lares of the city, Lararium publicum.

MACELLUM (#11)

The large building at the northeast corner of the Forum was a provision market, of the sort called macellum. Such markets without doubt existed in the Greek cities after the time of Alexander; from the Greeks, as in the case of the basilica, the Romans took both the name and the architectural type.

The first macellum in Rome was built in 179 B.C. in connection with the enlargement of a fish market.

The plan of the building is simple. A court in the shape of a rectangle, slightly longer than it is broad, is surrounded by a deep colonnade on the four sides.

Under this roof the fish that had been sold were scaled, the scales being thrown into the basin, where they were found in great quantity.

Behind the colonnade on the south side, and opening into it, was a row of market stalls or small shops.

Behind the colonnade on the south side, and opening into it, was a row of market stalls or small shops.

Above these were upper rooms, in front of which was a wooden gallery, but there was no stairway, and apparently the shopkeeper who wished to use his second story had to provide himself with a ladder.

We also find two rooms which gave to the building a religious character and placed it under the special protection of the imperial house. One, at the middle of the east end, is a chapel consecrated to the worship of the emperors.

The floor is raised above that of the rest of the building, and the entrance is reached by five steps leading up from the rear of the colonnade. On a pedestal against the rear wall, and in four niches at the sides, were statues, of which only the two in the niches at the right have been found; these represent Octavia, the sister of Augustus, and Marcellus, the hope of Augustus and of Rome, whose untimely death was lamented by Virgil in those touching verses in the sixth book of the Aeneid.

The macellum in its present form was at the time of the eruption by no means an ancient building.

While finished and no doubt in use at the time of the earthquake of 63, it had been built not many years before, in the reign of Claudius or of Nero, in the place of an older structure which dated from the pre-Roman period.

We can hardly doubt that Claudius was worshipped in Pompeii during his lifetime; it is known from inscriptions that even before the death of Claudius Nero was honored with the services of a special priest.

TEMPLE OF JUPITER/TEMPIO DI GIOVE (#12 )

Three temples adjoined the Forum at Pompeii. In addition, there was a sanctuary of the City Lares; and the temples of Venus Pompeiana and Fortuna Augusta were but a short distance away.

These religious edifices are representative of the different periods in the history of the city. In very early times, the Oscans of Pompeii received from the Greeks who had settled on the coast the cult of Apollo, and built for the Hellenic god a large, fine temple adjoining the Forum on the west side.

Several centuries later, the divinities of the Capitol—Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva—were enthroned in the temple that on the north side towered above the area.

Further north, in the first block at the right beyond the Forum, is the temple of Fortuna Augusta, the goddess who guarded the fortunes of Augustus, erected in 3 B.C. A chapel for the worship of Claudius and his family was placed in the macellum; this seems to have sufficed also for the worship of Nero.

Further north, in the first block at the right beyond the Forum, is the temple of Fortuna Augusta, the goddess who guarded the fortunes of Augustus, erected in 3 B.C. A chapel for the worship of Claudius and his family was placed in the macellum; this seems to have sufficed also for the worship of Nero.

After Nero's death and after the brief Civil War, a temple was built close to the shrine of the Lares in honor of Vespasian, the restorer of peace, the new Augustus. This was the last temple erected in Pompeii; it was not entirely finished at the time of the eruption.

In the second century B.C. the large and splendid Basilica, serving the double purpose of a court and an exchange, was built at the southwest corner.

Diagonally opposite, near the temple of Jupiter, a provision market, the macellum, was constructed; this also at an early date. It was entirely rebuilt in the time of the Empire, perhaps in the reign of Claudius.

On the west side, from pre-Roman times, stood a small colonnade in two stories, with its rear against the rear of the colonnade on the north side of the court of the temple of Apollo; only the first story, of the Doric order, has been preserved.

Probably this structure and the small open space in front were at first used as a market; later, in the imperial period, shops were built upon the open space, and the colonnade was made over into closed rooms, the purpose of which, except in the case of one, is unknown.

The temple of Jupiter dominates the Forum, and more than any other structure gives it character. It probably dates from the pre-Roman period, the columns being of tufa covered with white stucco.

The earthquake of the year 63 left the temple in ruins, and at the time of the eruption the work of rebuilding had not yet commenced.

The temple stands on a podium 10 Roman feet high, and including the steps, 125 Roman feet long. Very nearly a half of the whole length is given to the cella; of the other half, a little more than two thirds is occupied by the portico, leaving about a third (20 Roman feet) for the steps.

The pediment was sustained by six Corinthian columns about 28 feet high. This arrangement—a deep portico in front of the cella—is Etruscan, though the canon of Vitruvius, that in Etruscan temples the depth of the portico should equal that of the cella, is violated.

The high podium also, with steps in front, is characteristic of Etruscan, or at least of early Italic religious architecture.

On the other hand, the architectural forms of the superstructure are Greek, and these in turn have had their influence upon the plan. Just in front of the doorway, which was fifteen Roman feet wide, are the large stones with holes for the pivots on which the massive double doors swung; the doors here were not placed in the doorway, but in front of it, and were besides somewhat larger, so that the effect was rendered more imposing when they were shut.

The ornamentation of the cella was especially rich. A row of Ionic columns, about fifteen feet high, stood in front of each of the longer sides; the entablature above them probably served as a base for a similar row of Corinthian columns, the entablature of which in turn supported the ceiling. On the intermediate entablature, between the columns of the upper series, statues and votive offerings were doubtless placed.

The floor about the sides was covered with white mosaic, of which scanty remains have been found; the marble pavement of the center has wholly disappeared.

A head of Jupiter as found in the cella, as was also an inscription of the year 37 A.D., containing a dedication to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the ruling deity of the Capitol at Rome.

It is thus proved beyond question that the Capitoline Jupiter was worshipped here; and it will not be difficult to ascertain what other divinities shared with him the honors of the temple. As the Roman colonies strove in all things to be Rome in miniature, each thought it necessary to have a Capitolium—a temple for the worship of the gods of the Roman Capitol, Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva; and this naturally became the most important temple in the city.

That the worship of the three divinities was established at Pompeii is evident from the discovery of three images representing them, in the little temple conjecturally assigned to Zeus Milichius.

BATHS NEAR THE FORUM/TERME DEL FORO (#15 )

The bathing establishment in the block north of the Forum is smaller and simpler in its arrangements than that described in the last chapter, but the parts are essentially the same.

Here also we find a court, with a colonnade on three sides; a system of baths for men, comprising a dressing room with a small round frigidarium opening off from it, a tepidarium, and a caldarium; a similar system for women, the place of the frigidarium being taken by a tank for cold baths in the dressing room; and a long narrow furnace room between the two baths.

On three sides of the establishment are shops, in connection with which are several inns.

These baths were built shortly after 80 B.C., about the time that Ulius and Aninius repaired the Stabian Baths. The names of the builders are known from an inscription found in duplicate: “L. Caesius C. f. d[uum] v[ir] i[uri] d[icundo], C. Occius M. f., L. Niraemius A. f. II v[iri] d[e] d[ecurionum] s[ententia] ex peq[unia] publ[ica] fac[iundum] curar[unt] prob[arunt] q[ue]”.

Thus we see that the contract for the building was let and the work approved by Lucius Caesius, duumvir with judiciary authority and the two aediles, Occius and Niraemius, who are here styled duumvirs, for reasons already explained; the cost was defrayed by an appropriation from the public treasury.

The court here was not a palaestra; it was small for gymnastic exercises, and was not provided with a swimming tank and dressing rooms. The open space was occupied by a garden.

The colonnade on the north and west sides of the court had slender columns standing far apart, with a low and simple entablature; on the east side the columns were replaced by pillars carrying low arches, which served as a support for a gallery affording a pleasant view of the garden.

The colonnade on the north and west sides of the court had slender columns standing far apart, with a low and simple entablature; on the east side the columns were replaced by pillars carrying low arches, which served as a support for a gallery affording a pleasant view of the garden.

This gallery was accessible from the upper rooms of several inns along the street leading north from the Forum, whose guests no doubt found diversion in watching what was going on below—an advantage that may have been taken into account by the city officials in fixing the rent. From the court a corridor led into the men's apodyterium, which could be entered also on the north side from the Strada delle Terme. This room contained benches; but there were no niches, as in the dressing rooms of the Stabian Baths, and wooden shelves or lockers may have been used instead.

The small dark chamber at the north end may have been used as a storeroom for unguents, such as the Greeks called elaeothesium. Light was admitted to the dressing room through a window in the lunette at the south end, closed by a pane of glass half an inch thick, set in a bronze frame that turned on two pivots.

On either side of the window are huge Tritons in stucco relief, with vases on their shoulders, surrounded by dolphins; underneath is a mask of Oceanus blackened by the soot. The frigidarium is well preserved.

In all its arrangements it is almost an exact counterpart of the one in the Stabian Baths, with decorations suggestive of a garden.

The tepidarium is in the condition of the tepidariums of the Stabian Baths before the improved arrangements for heating were introduced. There were no warm air chambers in the walls or the floor.

The caldarium is well preserved; only a part of the vaulted ceiling has been destroyed. We learn from an inscription on the labrum, in bronze letters, that it was made under the direction of Gnaeus Melissaeus Aper and Marcus Staius Rufus, who were duumvirs in 3-4 A.D., at a cost of 5250 sesterces.

This room seems to have received its final form before the new method of heating the water in the alveus came into vogue; there is no trace of a bronze heater, such as that found in connection with the bath basin of the women's caldarium at the Stabian Baths. The simple decoration is in marked contrast with the usual ornamentation of the later styles.

The rooms of the women's baths are small, their arrangement being determined in part by the irregular shape of the corner of the building in which they are placed; but the system of heating is more complete than in the men's baths, for both the tepidarium and the caldarium were provided with hollow floors and hot air spaces in the walls extending to the lunettes and the ceiling.

The vaulted ceilings of both of these rooms, as well as of the apodyterium, are preserved; but the caldarium has lost its hollow floor and walls, together with the bath basin, which was placed in a large niche at the right as one entered; only the base of the labrum remains.

TEMPLE OF FORTUNA AUGUSTA/TEMPIO DI FORTUNA AUGUSTA (#16 )

Passing out from the Forum under the arch at the northeast corner, we enter the broadest street in Pompeii.

On the right a colonnade over the sidewalk runs along the front of the first block, at the further corner of which, where Forum Street opens into Nola Street, stands the small temple of Fortuna Augusta.

The front of the temple is in a line with the colonnade, which seems to have been designed as a continuation of the colonnade about the Forum. The colonnade is certainly not older than the earlier years of the Empire, and the temple dates from the time of Augustus.

The front of the temple is in a line with the colonnade, which seems to have been designed as a continuation of the colonnade about the Forum. The colonnade is certainly not older than the earlier years of the Empire, and the temple dates from the time of Augustus.

The divinity of the temple and the name of its builder are both known to us from an inscription on the architrave of the shrine at the rear of the cella: M. Tullius M. f., d. v. i. d. ter., quinq[uennalis], augur, tr[ibunus] mil[itum] a pop[ulo], aedem Fortunae August[ae] solo et peq[unia] sua,—'Marcus Tullius the son of Marcus, duumvir with judiciary authority for the third time, quinquennial duumvir, augur, and military tribune by the choice of the people, (erected this) temple to Fortuna Augusta on his own ground and at his own expense.

Such inscriptions were ordinarily placed on the entablature of the portico.

The worship of Fortuna Augusta was in charge of a college of priests, consisting of four slaves and freedmen, who were called Ministri Fortunae Augustae,—'Servants of Fortuna Augusta.'

HOUSE OF THE FAUN/CASA DEL FAUNO (#17)

The house of the Faun, so named from the statue of a dancing satyr found in it, was among the largest and most elegant in Pompeii. It illustrates for us the type of dwelling that wealthy men of cultivated tastes living in the third or second century B.C. built and adorned for themselves.

The mosaic pictures found on the floors (now in the Naples Museum) are the most beautiful that have survived to modern times.

The wall decoration, which is of the first style, in the more important rooms was left unaltered to the last, and is well preserved. This decoration, however, does not date from the building of the house.

In order to protect the painted surfaces against moisture, the walls in the beginning were carefully covered with sheets of lead before they were plastered.

An entire block, measuring approximately 315 by 115 feet, is given to the house; there are no shops except the four in front.

The apartments are arranged in four groups: a large Tuscan atrium, with living rooms on three sides; a small tetrastyle atrium, with rooms for domestic service around it and extending on the right side toward the rear of the house; a peristyle, the depth of which equals the width of the large and half that of the small atrium; and a second peristyle, occupying more than a third of the block.

At the rear of the second peristyle is a series of small rooms the depth of which varies according to the deviation of the street at the north end of the insula.

In front of the main entrance we read the word HAVE (more commonly written ave), 'Welcome!' spelled in the sidewalk with bits of green, yellow, red, and white marble.

The floor of the fauces, as of many of the other rooms, is rich in color. It is made of small triangular pieces of marble and slate—red, yellow, green, white, and black.

At the inner end it was marked off from the floor of the atrium by a stripe of finely executed mosaic, suggestive of a threshold, now in the Naples Museum. Two tragic masks are realistically outlined, appearing in the midst of fruits, flowers, and garlands, the details of which are worked out with much skill. The atrium was a room of imposing dimensions. The length is approximately 53 feet, the breadth 33; the height, as indicated by the remains of the walls and the pilasters, was certainly not less than 28 feet.

Above was a coffered ceiling. The somber shade of the floor, paved with small pieces of dark slate, formed an effective contrast with the white limestone edge and brilliant inner surface of the shallow impluvium, covered with pieces of colored marbles similar to those in the fauces. Still more marked was the contrast in the strong colors of the walls.

Below was a broad surface of black; then a projecting white dentil cornice, and above this, masses of dark red, bluish green, and yellow. The decoration, as usual in the first style, was not carried to the ceiling, but stopped just above the side doors; the upper part of the wall was left in the white.

As one stepped across the mosaic border at the end of the fauces, a beautiful vista opened up before the eyes. From the aperture of the compluvium a diffused light was spread through the atrium brilliant with its rich coloring.

At the rear the lofty entrance of the tablinum attracted the visitor by its stately dignity.

The shrubs and flowers of the garden are bright with sunshine, and fragrant odors are wafted through the house; in the midst a slender fountain jet rises in the air and falls with a murmur pleasant to the ear.

Of the rooms at the side of the atrium, one was apparently the family sleeping room; places for two beds were set off by slight elevations in the floor. This room had been carefully redecorated in the second style; the room opposite, the decoration of which was inferior to that of the rest, was perhaps used by the porter (atriensis).

The tablinum, like that of the house of Sallust, had a broad window opening on the colonnade of the peristyle. In the middle of this room is a rectangular section paved with lozenge-shaped pieces of black, white, and green stone; the rest of the floor is of white mosaic.

The floor of each ala was ornamented with a mosaic picture. In that at the left are doves pulling a necklace out of a casket—a work of slight merit. The mosaic picture found in the right ala is characterized by delicacy of execution and harmonious coloring. It is divided into two parts; above is a cat with a partridge; below, ducks, fishes, and shellfish.

A large window in the rear wall of this ala opens into the small atrium, not for the admission of light, but for ventilation; in summer there would be a circulation of air between the two atriums.

Two doors, at the right and the left of the tablinum, opened into large dining rooms, one nearly square, the other oblong. Both had large windows on the side of the peristyle, and the one at the left also a door opening upon the colonnade.

The mosaic pictures in the floors harmonized well with the purpose of the rooms. In one were fishes of various kinds, and sea monsters; in the other was the picture—often reproduced—in which the Genius of the autumn is represented as a vine-crowned boy sitting on a panther and drinking out of a deep golden bowl.

The colonnade of the first peristyle was of one story. The entablature of the well proportioned Ionic columns presented a mixture of styles often met with in Pompeii, a Doric frieze with a dentil cornice.

The wall surfaces were divided by pilasters and decorated in the first style. In the middle of the garden the delicately carved standard of a marble fountain basin may still be seen.

The open front of the broad exedra was adorned with two columns, and at the rear was a window extending almost from side to side, opening upon the second peristyle.

Between the columns of the entrance were mosaic pictures of the creatures of the Nile,—hippopotamus, crocodile, ichneumon, and ibis; and in the room, filling almost the entire floor, was the most famous of ancient mosaic pictures, the battle between Alexander and Darius.

The battle is perhaps that of Issus. The left side of the picture is only in part preserved. At the head of the Greek horsemen rides Alexander, fearless, un-helmeted, leading a charge against the picked guard of Darius. The long spear of the terrible Macedonian is piercing the side of a Persian noble, whose horse sinks under him. The driver of Darius's chariot is putting the lash to the horses, but the fleeing king turns with an expression of anguish and terror to witness the death of his courtier, the mounted noblemen about him being panic-stricken at the resistless onset of the Greeks. The grouping of the combatants, the characterization of the individual figures, the skill with which the expressions upon the faces are rendered, and the delicacy of coloring give this picture a high rank among ancient works of art. Alexander, having thrown aside his helmet, is leading the charge upon the guard of Darius, who is already in flight.

On either side of the exedra were two dining rooms, one open in its entire breadth upon the second peristyle, the other having a narrow door with two windows. In the sleeping room on the other side of the corridor, which had been redecorated in the second style, remains of two beds were found.

The room next to it was the largest in this part of the house; at the time of the eruption it was without decoration and was used as a wine cellar.

A great number of amphorae were found in it, as also in both peristyles.

The domestic apartments were entered by a front door between the two shops at the right.

The vestibule, unlike that of the other entrance, is open to the street.

This part of the house was much damaged by the earthquake of 63, and there are many traces of repairs, particularly in the upper rooms.

The kitchen is of unusual size. A niche for the images of the household gods was placed in the wall at the left, so high up that it could only have been reached by means of a ladder.

The front is shaped to resemble the façade of a small temple, and in it is a small altar of terra cotta for the burning of incense.

For printing our entire Pompeii Guide (facing pages) you can download the PDF by clicking HERE

For offline reading on your smartphone or tablet, you can download the PDF of our entire Pompeii Guide (single page) by clicking HERE

If you have an Android OS, you will find it in your Download app.

If you have an iPhone or an iPad, open and save it in iBook (free app).